This is where Sweden dug deep: for ore, for heat, for survival. Västmanland is part of Bergslagen, the historic mining district that shaped Sweden’s industrial backbone. The land shows it. Slag heaps, forest shafts, smelting towers. The city of Västerås sits at the edge of Lake Mälaren — a city shaped by trade, energy and steady work. Inland, the landscape shifts. You move through deep forest, past black lakes and quiet trails. Old power stations. Saunas built by welders. Places that do what they were made to do. The region doesn’t announce itself. But it holds. You come, you stay, you notice the ground. And that’s enough.

Lindesberg, Sweden

Review: In Between Trees

The Nordics • See & do • Review: In Between Trees in Lindesberg, Sweden

What’s the exhibition in a nutshell?

Swedish company Tormek makes sharpening systems. Water-cooled, slow-spinning grindstones used by chefs, woodworkers and craftspeople around the world. That’s their thing. But this summer, in a stark industrial hall in Lindesberg, a small factory town in central Sweden, they’ve staged something curious: an art show about trees. Curated by Daniel Wester of Trunk & Wise, ‘In Between Trees – Through Grind and Motion’ brings together Max Bainbridge, Emi Shinmura, Lélia Demoisy, Sanna Lindholm and Oskar Gustafsson – five international artists who carve, turn, cast and join wood into objects that sit somewhere between sculpture and ritual. It’s not necessarily visually pleasing in the way traditional woodwork often is; instead, it’s precise, deliberate and sometimes raw.

What is showcased?

Tormek’s two previous exhibitions, which started in 2023, have celebrated the edge – the sharpness of tools and the precision of the maker’s hand. ‘In Between Trees’ moves the frame. Curated by Wester of Trunk & Wise, the 2025 edition steps away from technique as subject and toward material as language. What it offers is a space for encounter.

The setting is spare and deliberate: sculptural works, each occupying its own position, surrounded by low light, ambient sound and projected images. The projections are not illustrative – they neither explain nor dramatise – but act as visual echoes, brushing walls and surfaces in slow rhythm. “We wanted to create a sense of immersion,” says Wester. “To move the visitor from admiration to reflection.”

A forest reduced, not replicated

Rather than recreate a forest, the exhibition dissects its elements. Each object becomes a stand-in, not for a tree itself, but for a specific relationship to trees: as structure, as cycle and as symbol. “The tree has always been central to human development,” Wester says. “It’s given us tools, vessels, warmth, shelter, movement. It’s in our earliest technologies. But it’s also in our myths – the tree of life, the seed and the annual return.”

This duality underpins the curatorial approach. Material and metaphor are treated as inseparable. The exhibition avoids narrative in favour of resonance. The tree is neither illustrated nor thematised: it is present, parsed and reframed.

Atmosphere as method

The spatial experience plays a crucial part. Wester and his team designed the exhibition as a constructed atmosphere. “We didn’t want to build a forest, but we wanted to let people feel inside one – emotionally, if not literally,” he says.

That atmosphere – sound, projection and pacing – is what allows the visitor to shift from object to field, from maker to material, from detail to whole.

A clear point of view

Wester’s artist selection is process-led. “I was looking for clarity of expression, but also for five distinct ways of approaching wood,” he explains. Each artist works with edge tools and uses a specific technique: turning, joining, hollowing, steam bending or casting. Each is also accustomed to slowness – to methods that resist speed, that privilege precision over productivity.

Crucially, all five make use of Tormek systems in their work. But the connection is structural, not promotional. The exhibition isn’t about the tool, but rather about the conditions that make the tool necessary. And what happens when material pushes back.

Five artists, five techniques

The exhibition begins in stillness. Suspended in the air, a large, hollowed-out section of tree trunk hangs at an angle, its surface stripped but not polished. It floats heavily, if such a thing is possible – weight made momentarily weightless. Below it, a jagged bronze form rests on a low plinth. The metal is deeply textured, as if frozen mid-twist. This is ‘Heartwood II’ by Max Bainbridge (UK), who works with wood and cast bronze to trace what trees contain – structurally, emotionally, historically. The pairing is deliberate. One piece holds space, the other holds density.

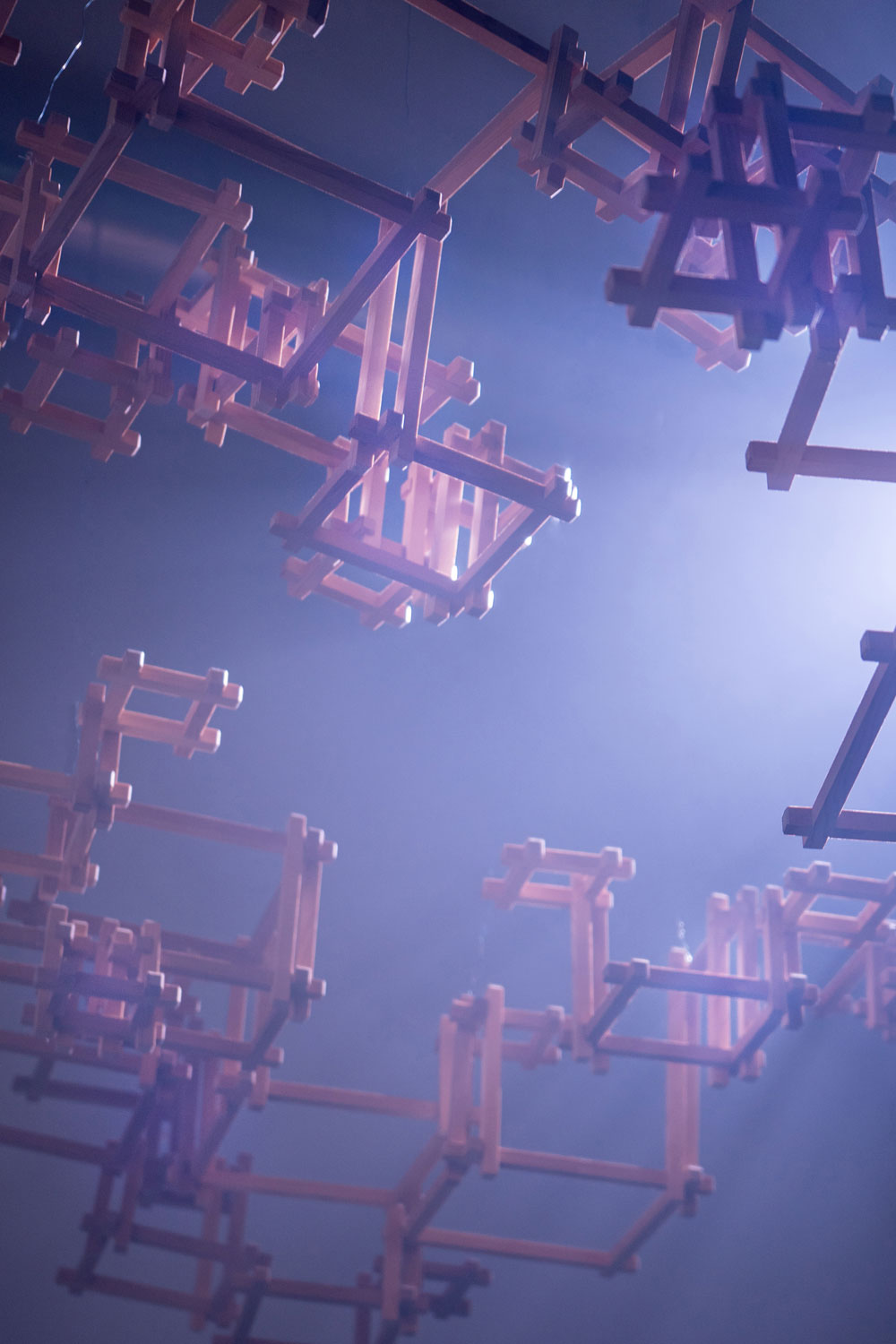

Above, a cloud of wooden units hovers in midair – each piece cut, notched and joined into an open, geometric lattice. The structure shifts as you move beneath it, forming loose constellations that feel almost digital. This is ‘Crown Shyness’ by Emi Shinmura (Japan/UK), a work built entirely through traditional Japanese joinery. The precision is extreme, but never showy – each intersection is both mechanical and expressive. Like pixels suspended in space, the modules seem to search for connection.

Thick, dark forms rise from the ground in looping arches, their shapes both familiar and distorted. Branches extend awkwardly from trunks that curve in unnatural directions, as if grown under pressure or caught mid-movement. This is ‘Back to Earth’ by Lélia Demoisy (France) – a sculptural installation that brings forest material into the room. Built from real wood and bent by hand, the piece is physical, heavy and tactile. Demoisy’s practice centres on our closeness to nature as shared condition.

Five wooden forms hang from the ceiling, turned and carved into elongated spirals that taper at both ends. They recall plumb bobs or bells – tools for sensing weight, direction or depth. These are from ‘Lod’ by Sanna Lindholm (Sweden). On the floor, ‘Nattsång’ sits lower and darker, with a burnished, almost metallic surface that reflects the room’s ambient light.

A wooden coil lies on the floor, its surface warped, stitched and pieced together with copper wire. It looks like it’s been forced into shape – bent, bound, held together under pressure. This is ‘Tillvarons Hierarkier’ by Oskar Gustafsson (Sweden). The piece feels bodily and defensive, as if bracing itself. Gustafsson often explores the relationship between tree, body and terrain, and here that connection is pushed to the edge. It’s not graceful – it’s strained, and that’s the point.

What is the setting like?

Lindesberg is a small industrial town in Bergslagen, more associated with engineering than exhibitions. But it’s here, inside Tormek’s own factory building, that ‘In Between Trees’ takes place – in the company’s own exhibition hall, just steps from the production floor.

“This is the third in a series of annual exhibitions we’ve done here,” says CEO Samuel Stenhem. “It started in 2023, when we turned 50. We wanted to celebrate by inviting the artists and makers we’ve built relationships with over the years and show what can be done with truly sharp tools.”

“With ‘In Between Trees’, we’re taking a step closer to the artistic and the spatial,” he explains. “In a way, it’s also a nod to my previous role as an art director, where creativity and ideas were always part of the work. This is a chance to highlight creators in a new way.”

Where it’s made matters

Tormek’s machines are made in-house. That’s central to how the company sees itself. “I usually say that Tormek is real,” says Stenhem. “It’s here in Lindesberg that we produce our sharpening systems.” The exhibition space sits next to a small museum and concept store, open during gallery hours. “Being part of the local community is important to us,” he adds. “On an international level, being Swedish matters. On a national level, being local matters.”

While putting on an exhibition isn’t in Tormek employees’ job descriptions, the team has taken it on with enthusiasm. “Our staff are fantastic,” he says. “Events and exhibitions aren’t really part of our core work, but it’s clear that people enjoy doing them. It brings a kind of extra energy.”

A tool and a meeting point

Each exhibition ends in a gathering of artists, craftspeople and creators. They come from different disciplines but share a common need. “That shared moment, around the sharp edge, is where it all comes together for us,” he says. “Those meetings are incredibly inspiring. It’s something we’ll absolutely continue. The exhibition hall will keep filling with interesting objects and people.”

What’s our final take?

What’s striking about ‘In Between Trees’ is not just the international standard of the exhibition, but where it takes place: deep in Sweden’s Bergslagen region, inside a sharpening factory. Across the Nordics, production sites are reimagining their own relevance, not only acknowledging their cultural weight but building structures around it. At Vestre’s The Plus in Magnor, Norway, or Kvadrat’s headquarters in Ebeltoft, Denmark, manufacturing is framed as a form of public engagement. Tormek’s approach is smaller, but no less considered. The decision to invite Trunk & Wise to lead the curatorial process suggests a willingness to be challenged. The result is measured, confident and unusually sincere. The artists, for their part, meet the space with gravity rather than spectacle. This is truly what sharpness looks like.

What’s the region like?

Details

Tormek

Skogstorpsvägen 3A

Lindesberg

Sweden

Photography courtesy of Trunk & Wise and Tormek

Urban

Rural

Trendy

Classic

Happening

Serene

Affordable

Lavish

Share this

Details

Tormek

Skogstorpsvägen 3A

Lindesberg

Sweden

Photography courtesy of Trunk & Wise and Tormek

Urban

Rural

Trendy

Classic

Happening

Serene

Affordable

Lavish