The Nordics

Trend watch: how the Nordics are turning second-hand into high design

The Nordics • Insider guides • Trend watch: how the Nordics are turning second-hand into high design

Second-hand – from charity-shop stigma to design studio status

Table of Contents

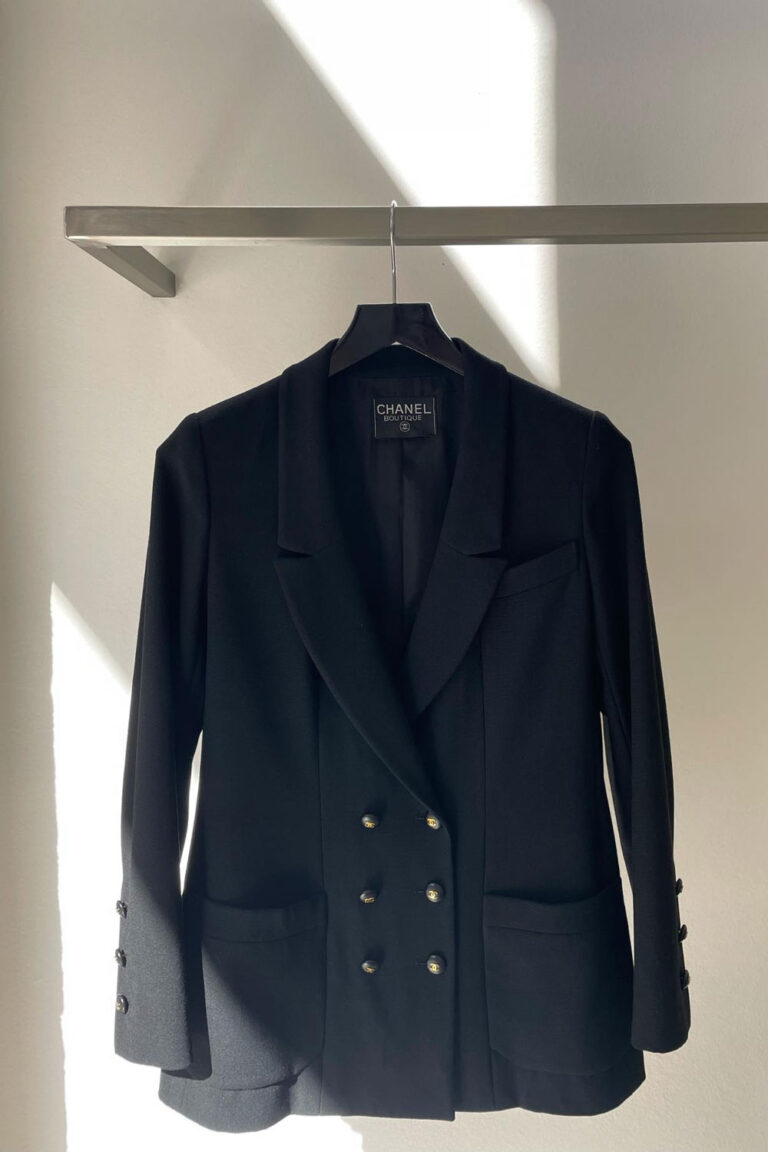

Top photography courtesy of Lola Legacy

How has second-hand shifted in the Nordics?

We’re seeing a wave of innovation across the Nordic second-hand scene. Stockholm’s Lola Legacy is a flagship example, but it’s far from alone. Arkivet offers trend-responsive picks in Stockholm, Schultneck blends fashion and florals in Gothenburg, A Retro Tale serves authenticated luxury in Stockholm and Relove Second Hand & Café merges café culture and curated resale in Helsinki – and even at the airport.

According to Euromonitor, the share of Nordic consumers who buy second-hand every few months rose to 27 per cent in 2024, up from 23 per cent in 2019. Meanwhile, the share of people who have never purchased pre-owned goods dropped to 15 per cent. Tradera, Sweden’s largest resale marketplace, grew its revenue 26 per cent between 2021 and 2023, underscoring the category’s strength.

These figures show one truth: second-hand is no longer fringe – it is very much mainstream and shaping up to be a serious challenger to traditional fashion retail.

Designing second-hand differently

Lola Legacy’s ambition was clean from the outset. “We wanted the joyful, unexpected side of second-hand,” says Bengtsson, who founded it with partner Lisa Lindh. She speaks of an “ever-changing selection” featuring pieces from many eras. But she was also conscious of common stereotypes – second-hand can feel “complicated, time-consuming or even unclean.”

The shift wasn’t just about what they sold, but how. “We chose a name that doesn’t scream ‘second-hand’,” she explains. “A name sets tone and influences perception.” Lola Legacy suggests heritage and imagination, not morality or compromise.

Step inside and the design speaks. The store looks and feels like a design studio, not a thrift shop. Bold colours, considered displays and a sense of care give each garment room to breathe.

What’s happening in stores is part of a larger ecosystem shift. Online platforms like Tradera and Vinted are fuelling volume. Physical stores are experimenting with editorial curation, shops doubling as cafés and luxury-grade authentication. The data, both from consumer behaviour and economic projections, points clearly to a second-hand economy that’s bigger, more stylish and more integrated than ever before.

Photography courtesy of Lola Legacy

Are we stepping away from the word ‘sustainable’?

The Nordics have long been testing grounds for new approaches to fashion, from early textile recycling pilots to strict government targets. But today, the word “sustainable” itself is under review. The problem isn’t that sustainability matters less – it matters more than ever. It’s that the term has been overused, stretched to cover everything from organic capsule collections to recycled polyester hang-tags. The result is a word that no longer sparks much trust or excitement.

Making it implicit rather than explicit

This shift is visible across the region. At Copenhagen Fashion Week, sustainability criteria are now part of the entry requirements, so every brand on the schedule already meets a minimum standard. Yet very few actually lead with the word. Instead, they talk about craft, longevity, innovation and design integrity.

In Finland, Marimekko’s communication focuses on timelessness rather than slogans. In Sweden, Filippa K speaks about longevity and circular design. Danish label Samsøe Samsøe highlights responsibility but frames it through style and craftsmanship. What was once the headline has become the subtext.

Bengtsson sees the same risk at the brand level. “If we had chosen a name with words like second-hand, circular or pre-loved, we would only have reinforced the picture many people already have of resale,” she explains. “That image doesn’t align with ours, and it gives us a much longer starting distance before we can even explain who we are and what we do.” For Lola Legacy, the choice was about avoiding judgement before contact. “Some people have found it confusing, but that’s what happens when you meet something new and unfamiliar.”

Leading with aesthetics

Rather than pointing to carbon savings or circular systems, Lola Legacy leads with atmosphere, edit and design. “We’re not sustainability profiles,” Bengtsson admits. “We know a lot, but what we know much more about is aesthetics, inspiration and how to transform something ‘ugly’ into something beautiful.”

This reframing makes second-hand less about duty and more about desire. “We also want to convey a story about the clothes – where they come from, maybe even who has worn them,” Bengtsson says. For her, the notion of legacy and inheritance carries positive weight. “Just like in art, heritage can create a greater product value – hopefully something the buyer can also pass on.”

This softening of “sustainable” is not a retreat from responsibility but a recalibration of how it is expressed. The Nordics are once again setting the tone: sustainability is embedded, assumed and made visible through form, craft and provenance rather than buzzwords. The result is communication that appeals to emotion, taste and culture: making people fall in love with reuse first, and feel good about its footprint after.

And what about the word ‘second-hand’ – is it still relevant?

The word itself still matters. It gives clarity and it avoids evasiveness. “We absolutely use the word second-hand when talking about the product,” says Bengtsson. “It’s important to be clear. You don’t need to be coy about what you’re selling.”

But clarity is not the same as branding. In communication, Bengtsson and her partner have chosen to tone it down. For them, the word carries too much baggage – years of associations with bargain basements, charity shops and compromise. Leading with it would only reinforce the very image they are trying to move away from.

Pre-loved, circular, reused …

Across the industry, softer terms have emerged: pre-loved, circular and reused. They attempt to nudge perception away from scarcity and towards care. Lola Legacy acknowledges the shift but rarely adopts the vocabulary. “Pre-loved is now an established expression, and of course it suggests a more positive view of second-hand. We like it, but we hardly ever use it,” Bengtsson explains.

What they prefer instead is to talk about the garment itself — its content, material, history or a striking detail that makes it worth noticing. That narrative gives the piece a different weight. “It creates a story that builds a relationship and gives the garment a chance to become more than just second-hand,” she says.

Photography courtesy of Lola Legacy

What makes someone choose a second-hand item today?

The reasons people choose second-hand across the Nordics are widening, and they vary by age, country and circumstance. What was once framed as bargain hunting now spans sustainability, health, aesthetics and tradition.

Regional habits and traditions

In Denmark, younger generations are the most active resale consumers, treating second-hand as a normal part of everyday shopping. The Oslo-based app Tise has reinforced this behaviour across borders. In Finland, the long-standing flea market culture – kirpputori – has kept reuse visible and practical, and platforms like Tori.fi make it easy for families to manage the constant turnover of children’s clothing. In Norway, awareness of textile waste has become a driver, with campaigns around overproduction pushing more people toward reuse. Sweden, meanwhile, has leaned into digital resale, with Tradera and Sellpy making it seamless for even first-time buyers to take part.

Motivations in the store

Bengtsson sees these broad patterns reflected locally. Some customers act from principle, others extend long-held habits into children’s wardrobes, and more recently parents have shifted because of health concerns over chemicals in new clothing. Grandparents often buy with both thrift and perspective, while first-time visitors sometimes mistake the garments for new stock. “Most of the time they’re positively surprised,” she says. “They find the selection inspiring, and that’s when we feel mission accomplished.”

What unites these groups is not a single driver but a convergence of reasons. For some it’s sustainability, for others affordability, style or health. Together, they signal a cultural shift: second-hand in the Nordics is no longer one thing, but many things at once, and that diversity is what is pushing it into the mainstream.

Photography courtesy of Schultnek

How do retail spaces shape how people feel about reuse?

In the Nordics, design is part of everyday life. From Arne Jacobsen’s furniture to Alvar Aalto’s architecture, the region has long treated form and function as inseparable. That sensibility extends to fashion retail. The way clothes are displayed, the atmosphere of a shop, even the colour of a wall all carry weight. And in second-hand, where perception has always been fragile, design is more than decoration. It can be the difference between stigma and status.

Bengtsson is clear about it: “Atmosphere and environment are everything. Some people are more conscious of their surroundings than others, but it affects all of us in how we feel and how we perceive things.” A cardboard box filled with wrinkled shirts signals low value before a customer even touches the fabric. By contrast, a carefully pressed garment, displayed with intention, immediately looks more desirable.

Design as elevation

This principle is embedded in Lola Legacy’s store, as well as many other retail spaces around the Nordics. Strong wall colours and distinctive interiors set it apart from the pastel palette common in children’s shops. “Just because we sell products aimed at children doesn’t mean the interior has to look like classic kids’ décor,” Bengtsson explains. Instead, the shop is designed with adults in mind, giving garments a sense of seriousness and presence. The effect is twofold: the bold background calms the constantly changing assortment while allowing individual pieces to stand out.

Children, too, respond to design. “They’re drawn to our strong colours, reflective materials and selected design elements,” Bengtsson says. For her, this is a hopeful sign – the next generation already learning that second-hand can feel exciting and valuable.

Photography courtesy of Lola Legacy

What directions will shape the future of second-hand in the Nordics?

Predicting fashion’s future is always precarious, but the trajectory of second-hand in the Nordics is becoming clearer. What was once a niche counterpoint to mainstream fashion is developing into a parallel system, one that could soon stand as a genuine competitor to fast fashion – or at least a credible counterweight.

“We believe what we see now is just the beginning,” says Bengtsson. “Second-hand and upcycling can compete with fast fashion. Or at least become a relevant opponent.”

A question of supply

Yet there is a catch. Nordic newspapers have pointed out that demand for second-hand now outstrips supply, especially when it comes to quality garments. Too much of what enters the resale system is poor in material or condition, making it difficult to meet rising expectations.

This scarcity highlights the limits of reuse alone – and explains why local production, textile innovation and upcycling are becoming so central to the conversation.

Localising production

One important shift is the conversation around local production. During Stockholm Fashion Week in the summer of 2025, the topic of bringing clothing manufacture back to Sweden gained traction.

The argument is practical: closer production chains make reuse easier, communication smoother, margins of error smaller and orders more flexible. Adjustments to design become easier, while transport and fees are reduced. For Bengtsson, this has clear implications for upcycling. If garments are produced nearby, reworking or reusing them becomes far more realistic.

Innovation in sorting and reuse

Technology is also reshaping the field. Siptex in Malmö, the world’s first industrial facility for automatically sorting textiles by fibre, shows how infrastructure can underpin a circular system. Smaller initiatives such as Flöde, developing new textile-sorting innovations, point in the same direction. “All these initiatives, large and small, have the potential to influence the conversation and set an example for other countries,” says Bengtsson.

Finland at the forefront

Regional differences matter too. Finland has long combined design with everyday pragmatism, and today it is positioning itself as a leader in both art and fashion. “It’s fascinating to see Finland at the forefront,” Bengtsson observes. The new Helsinki Biennial and the Fashion in Helsinki platform both suggest a country experimenting with cultural and material reuse in tandem.

Regulation as accelerator

Policy is about to push things further. Within two years, EU rules will require a digital product passport for all garments. Every item will need to show its entire production chain, from raw fibre to final stitching. “This is a big step when it comes to accountability,” Bengtsson says. “It will hopefully push larger companies to review their own manufacturing.” Transparency at this scale could normalise reuse, making it a routine part of fashion’s lifecycle.

Photography courtesy of Mikael Lundblad and A Retro Tale

Share this

Stay in the know

Sign up for the latest hotspot news from the Nordics.